On November 30, 2021, the French government rightly decided to grant the highest honor of being buried in the Panthéon to the American-born dancer and singer Joséphine Baker. Of the 80 personalities that lie in this mausoleum, she is the sixth woman and the first black woman and performing artist to receive this recognition. She will rest alongside other icons of the nation, such as Émile Zola, Victor Hugo, Marie Curie, Voltaire, Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Simone Veil. The day of the event was not chosen randomly, it marks the anniversary of the artist's acquisition of French nationality from her, in 1937, when she married Jewish industrialist Jean Lion (born Levy).

One of the reasons for this recognition is the role of resistance and militant against anti-Semitism that she played during World War II. In occupied France in 1940, after General de Gaulle's June 18 appeal, she refused to sing for the Nazis and became a spy for the Free French Forces, serving as a cover for Jacques Abney, head of counter-espionage, during their international tours. She also sang at the front lines to cheer up the soldiers and conveyed secret messages camouflaged with invisible ink on her sheet music and even on her cleavage. When she accepted her mission, she confided to Abney: It is France that made me what I am, I will hold her in eternal gratitude. France is sweet, where it is good for us people of color to live, because there are no racist prejudices. Didn't I become the darling of the Parisians? They have given me everything, especially her heart. I have given them mine. I'm ready, captain, to give them my life. You can dispose of me as you wish. For her contributions, she received in 1943 from de Gaulle a gold Cross of Lorraine, which she decided to sell at auction for 350,000 francs to benefit the Resistance; and after the war, the Legion of Honor and the Resistance Medal.

She is also worthy of being remembered for her role in fighting segregation in her home country. Born in 1906 in St. Louis, Missouri, she suffered all the torments to which her race was subjected. Abandoned by her father, a black honky-tonk musician of Spanish origin, she was mistreated by her half-black, half-Appalachian mother, who sent her to work as a servant at the age of eight. At thirteen she got married, and the following year she was already divorced twice, taking as her only asset the surname of her second husband, blues guitarist Willie Baker. She said that she later lived on the streets of San Luis, eating leftover garbage and dancing so as not to die of cold. When already famous she undertook a tour of the United States, she was the first to break segregation in Las Vegas, but she became an FBI persona non grata when she denounced the owner of the Stork Club in New York, who after allowing her to sit in his local refused to serve her because she was black. After the incident, he changed the lyrics of his famous song “J'ai deux amours, mon pays et Paris” (I have two loves, my country and Paris) to “J'ai deux amours, mon pays c'est Paris” (I have two loves, my country is Paris). And in 1963, dressed in her uniform and her French military medals, she campaigned against racism at the March on Washington for civil rights, during which Martin Luther King gave his famous “I have a dream” speech. She was, in fact, the only woman to deliver a speech during the demonstration. At this time, in France, she was already militating at a private level so that "there is only one human race"; she had adopted twelve children of different origins and cultures to form in her castle of Les Milandes, what she called her “rainbow tribe”, the realization of her ambition to give life to hers her “ideal of universal brotherhood”.

In the Gladys Palmera Collection, we also want to highlight her role as her black diva. She was a pioneer who opened the way in Europe to the acceptance of Afro and exotic arts: Afro-American dance, West Indian music, Afro-Cuban rhythms, African frenzy. Before arriving in Paris, she had been struggling as a vaudeville artist in the United States for five years. She first in a trio of street performers, the Jones Family Band, and then with the Dixie Steppers, until she reached Broadway by participating in the black musical “Shuffle Along”. After a tour, she joined the Chocolate Dandies in 1924 and later entered the Plantation Club, where she fascinated the wife of a commercial attaché at the United States embassy in France, who decided to hire her to present her in Paris, an eldorado for black artists, and "make her a star." She debuted in the French capital on October 2, 1925, at the Revue Nègre.

Her exotic way of dancing the charleston and her uninhibited "wild dance" in which, dressed only in a waist made of fabric bananas, she was inspired by animals such as the snake, the panther or the monkey, were an immediate success and saved the Bankruptcy Champs-Elysées Theater. She became the sensation of the moment, the icon of women's liberation in those crazy years when dresses and hair were getting shorter. In 1927, at just 21 years old, he was already leading the Folies Bergère, setting up his own cabaret (Chez Joséphine) and appearing in his first film La sirène des Tropiques, which would be followed by Zouzou (1934) and Princesse Tam Tam (1935), in the one that dances a wild rumba.

In 1930, her first records came out, and in 1936 she recorded accompanied by the Lecuona Cuban Boys, two congas by Armando Oréfiche, Mayarí and La conga Blicotí. A Columbia-brand 78 rpm disc treasured in our collections dedicated to Afro-Caribbean music; as well as some of the photographs of her taken during her trips to Cuba by Armand, the photographer to the stars, in the early 1950s; or the long-play that she recorded in 1966 at the Egrem studios in Havana, under the musical direction of Tony Taño. But at Gladys Palmera, we wanted to acquire something more from the “Ebony Venus”, something as unique as her, something that was not mass-produced objects. First in October 2018, it was a pair of shoes that belonged to her: a model created especially for her in the 1950s by Aurèle, a master shoemaker, and made up of 158 multicolored and wavy pieces of lambskin. And a year later, we acquired at auction in Saint-Jean-de-Luz, in the French Basque Country, a batch of 55 glass negative plates attributed to Walery and Varsavaux, depicting music-hall artists of the 1920s.

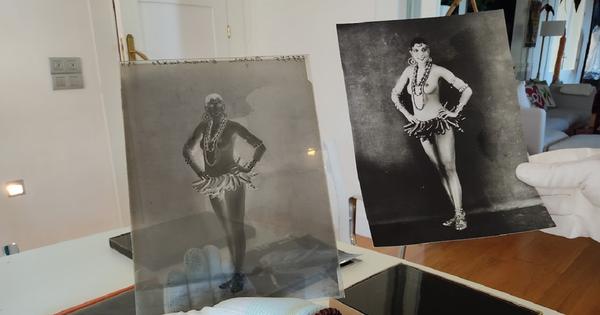

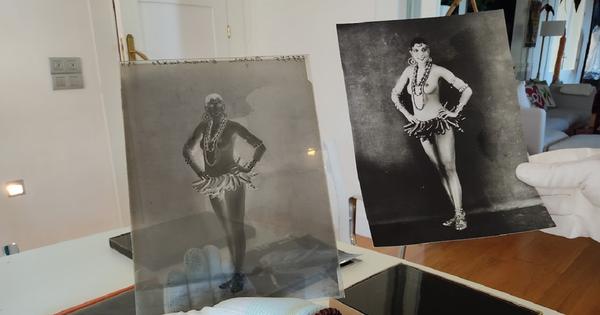

In this set, in addition to Mistinguett's plates, we find some extremely important objects, testimonies of Joséphine Baker's debuts: the original negatives of some of the first iconic photographs of her taken in 1926 by the Walery studio. To be more precise, a 18 x 24 cm “full plate” view, in which she poses with feathers, and another of the same size but divided into two views in which she shows off her famous banana waist. These negatives were used, after the success of the diva, to publish promotional postcards and to illustrate pages of the Paris Plaisir magazine, which we also keep in our library.

The expert in old photographs, Rubén Morales, conservator-restorer of photographic heritage, confirmed the exceptional nature of these negatives: They are indisputably original and unique pieces. And also very well preserved. You should always make a digital copy in case they degrade. It is true that glass holds better than plastic. There is always the risk that they will break and have their silver mirror, but the image will not be lost for many years. In fact, these plates have been around for almost a century and, by assembling a special set, excellent reproductions could be achieved. Other characteristics of these plates are the retouches: you can see how they used graphite. It was a very sharp pencil with which they blurred some areas and contours of the models that they considered unsightly. You can also notice some plaques that have a red mask. This also served to slim down the models. You can see that they retouched everything, to the full: the veins of the hands and feet, the neck, the wrinkles, the expression line, the shoulder, the knees. In a large studio, like Walery's, which photographed stars, they probably had a team of retouchers. He didn't do it himself. In the case of the Joséphine Baker plates, they had very little work, there are very few retouches; that is to say that either she had a body considered perfect for the established canon of beauty of the time, or with her a new canon was established. In the divided plate, they took advantage of the same plate to make two consecutive shots. They had a target with a mask on. So, they took one picture, moved the lens and shot the other.

With the conservation of these glass negatives in the Gladys Palmera Foundation-Collection, we hope, on our scale, to perpetuate the memory of a militant of all freedoms and an icon of all black music.

Log in with your user Gladyspalmera or with one of your social networks to leave your comment.

Log in