It was like a “gay Noah's ark”, a mafia-run dive, a late-'60s night haunt where gay New Yorkers could be themselves, let loose, and dance like few others could. places of the city.

It was the Stonewall Inn, a bar located at 51 and 53 Christopher Street in the Greenwich Village neighborhood.

His fame dates back to the night of June 28, 1969, when a police raid led to confrontations between agents and customers, who said enough was enough.

“It changed everything. Gays had pride, but it wasn't pride in being gay, it was pride in being themselves, it was individual pride. After Stonewall "it became a collective pride," says Martin Boyce, one of the bar's regulars who participated in those riots.

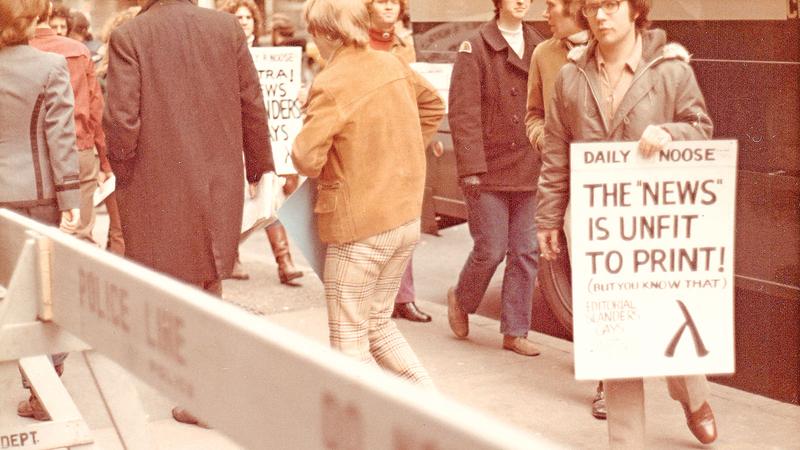

The riots were not the first nor would they be the last, but they were the catalyst for the still timid movement for the civil rights of the LGTBI community in this country that, a year later, called what would end up being the first Gay Pride March to commemorate that rebellion and condemn police brutality.

“Stonewall turned a small, localized movement into a large national movement that spanned the globe,” explains Eric Marcus, writer of the book “Making History: The Struggle for Gay and Lesbian Equal Rights 1945-1990” ( "Making History: The Struggle for Equal Rights for Gays and Lesbians 1945-1990").

The current location, reopened in 2007, is a memory of that symbol of the explosion of the LGTBI movement. Its current owners Kurt Kelly and Stacy Lentz describe it as "a gay church", as "a circus with lots of fun" with which they want to "recover the battered history" of the old venue.

For Boyce, the Stonewall is more than just a place to remember: “It's a verb, an action word.”

“Before Stonewall, it was too risky to come out. In the 50s and 60s you could lose your job, your family, even your house, ”says Marcus from the living room of his house, in the Chelsea neighborhood.

“New York was completely different. It was like a film noir, a dark city, not as bright as it is now, and in which all the laws were directed against homosexual people”, recalls Boyce.

Homosexuality was considered a mental illness in this country until 1973 and, in New York, electric shock treatments were not officially abolished until that same year.

Gay relationships, public displays of affection, and dressing in clothing of the opposite sex were prohibited.

“The bar was a dump, ugly, with no running water behind the bar. If you knew the bar and you had a bottle of beer or a can, you cleaned them because you could get hepatitis from the drinks. It wasn't much, but we were happy”, says Boyce, who in those days went to the bar dressed as a “terrifying drag queen”.

Most of the similar bars were near the ports, on lonely and dangerous streets, but the Stonewall was in the middle of vibrant Greenwich Village and had a dance floor, which was also forbidden for gays.

“Everyone went to the Stonewall because of how unusual it was for a place with music and where you could dance.” Boyce especially remembers the black drag queens who controlled the music machine, supervised the songs and kept the track alive. “If you played something they didn't like, you never went near the record player again,” he says.

Since it was not allowed to serve alcohol to people with “disorderly conduct” -a definition that the authorities used to refer to the gays they arrested-, the mafia gradually gained control of these places. “We always stayed away from the mob people we saw in the bar, even though their presence wasn't very obvious,” Boyce, then 20, says wistfully.

The Stonewall opened its doors in 1967 as a “private” business, the name by which the places frequented by the gay community were known. Between 1934 and 1964 it was a bar-restaurant with the same name, but it closed after a fire that destroyed its interior. The new owners simply painted the walls and windows black before reopening it to New York's gays.

Her clients ranged from executives in suits, who often stood by the entrance, to drag queens, to “street kids” like Boyce, to young teenagers, many of whom had been disowned by their families and who had made the streets and the night their life in the city.

“There were different kinds of gay people (…) It was like Noah's gay ark, there were a bit of all kinds of people. If there had been a flood, the gays would have been saved”, summarizes Boyce.

Given the situation, with riots in other places, murders of LGTBI people and a context of social movements in defense of disadvantaged groups, what happened on June 28, 1969 at the Stonewall was not a surprise. “It was just the night that the fuse was lit,” says Marcus.

Boyce wasn't there when the police broke in, but he was there, along with a friend, when they began to evacuate the clientele. “We went to look. I could see the drag queens coming out of the bar and waving. Then the people who felt ashamed always came out, the ones who had been caught unawares and feared being exposed.

Everything was going as on previous occasions in so many other gambling dens in the city. But then, as a policeman was pushing someone into the van, "a shoe with heels appeared and kicked him back."

After a moment's indecision, the officer got inside, and from outside, witnesses heard the noise of “flesh and bone hitting metal” from inside the vehicle. "You've seen the show, now get out of here," said the Policeman, trusting that they would leave, as they always did. But this time it was not like that.

“For some reason I can't explain even now, we started to take steps towards him. I don't know what we looked like because none of us turned to see the faces of the others. The policeman grabbed his baton and was going to speak again, but didn't. He saw something in us that scared him. He blinked, swallowed and headed into the bar," he says.

Some activists remember drag queen Stormé DeLarverie as the first to resist, but according to Boyle, the riots occurred at different points at the same time and in a confined space, “because there had been enough provocation from the police to get it all started.

When the cops ran into the Stonewall, things got out of control: “We all went crazy. First we threw them pennies, which were copper (copper) and was also the first name of the Police (“coppers”), and then we started throwing more serious things until our pockets were empty.

Hundreds of people joined the protest and riot forces showed up. “Nothing is louder in a riot than silence, and the whole street fell silent. Only a march was heard, a loud noise of troops. All the people who were there opened up and there they were”, says Boyle, as if he were reliving that night and had not narrated it in recent years.

It was then -he continues- that one of the most memorable moments took place: When the reinforcements arrived, the protesters grabbed each other forming a line and, before the astonished gaze of the agents, began to dance raising their legs while they sang the song “We are the Village's girls”.

Before the song ended, there was the dreaded police charge in which Boyce received a blow to the back that he was unaware of until the next morning. The altercations continued and did not come to an end until "daylight began."

“There were casualties, but a lot of casualties,” he says with a laugh. "Unfortunately they were friendly fire, because they hadn't taught us how to play baseball or things like that, so when we threw a brick we used to hit another gay guy."

At that time, pacifists, blacks, feminists were on the warpath, but the LGTBI collective never thought of itself as such. "We didn't have a book or a creed or anything like that, and we were so diverse that we weren't even united, so there was no way to find a way out of that situation."

According to Boyce, “If it hadn't been for the organizers who came along after the Stonewall, who planned the first march [of gay pride in commemoration of the riots], and who formed some of the militant organizations, the Stonewall would very likely have disappeared. of history”.

He is referring to the first march, the one that catapulted what happened in this bar and kept the flame of the movement for LGTBI rights burning forever. “That 1970 protest in Central Park was the largest gay rally in all of history,” Marcus recalls.

Kurt Kelly and Stacy Lentz, two of the owners of the current Stonewall, which occupies part of the space of the old gay club, assure that they want to preserve and maintain its spirit and the struggle of the movement LGBTI.

“We wanted to bring history back, that he was treated and respected as he should, because he wasn't,” says Kurt, sitting at the bar on the top floor, an addition to the original space. Since it reopened under her management in 2007, the goal is to keep it "at the forefront of the fight for the rights of the gay movement," adds Lentz, a lesbian activist who made sure that the new bar had a place for women.

“The Stonewall was not a place for women to go, even in the 1990s, when it reopened as a gay bar. But, fortunately, we as a group have worked to let lesbians come here and give them a place", says the activist, who assures that in New York there are 55 bars that define themselves as gay places for men, two "as a kind of mix” and another as “purely lesbian”.

“We are a movement. When we took over, our goal was to make this a gay church, where everybody could come and rejoice and everybody could grieve,” Kelly adds. Although it is also like a "circus", with drag shows, concerts and cabaret, remember.

Today, the Stonewall is gleaming, with a wainscoting ground floor and billiards; an upper floor with another bar counter and rainbow flags hanging from the black ceiling and a façade also full of small multicolored banners of the LGTBI movement.

Visits from personalities such as Irish Prime Minister Leo Varadakar and his partner Matt Barrett in 2018 or the performance of singer Madonna last New Year's Eve have only boosted its popularity.

A fame that its owners hope will not surpass them with the arrival of millions of tourists to New York to participate in the celebration of the World Pride March, this June 30, which will also mark the 50th anniversary of the rebellion of the customers of that gay club.